Finding a different way of construing a situation or event – including taking another perspective on something emotionally difficult – is itself a form of creativity.

Research points to many similarities between our ability to cognitively reappraise emotionally-charged events, and well-established creative processes such as insight and flexible reinterpretation.

Introducing the idea of “reappraisal inventiveness”

Imagine yourself in the following brief scenario:

You arrive at your apartment after having been on a long vacation. You had asked a friend of yours to water your plants while you were gone. Now you see that most of your plants have died. You call your friend. She tells you on the phone that the distance to your apartment was too long for her to water your plants as agreed.

What are all of the ways that you can think of to diminish your frustration, anger, and disappointment with your friend, and the loss of your plants?

The scenario is one of several such scenarios taken from the research materials of a team of researchers at two universities in Germany (Weber et al., 2014).

In the study, participants were given three minutes to write down all of the ideas they could bring to mind to alleviate their negative emotions to this and other scenarios.

The researchers found that individuals who were more adept and successful at finding different construals of this and other emotion-inducing situations also demonstrated other indications of creativity. They were, for example, more likely to generate many and varied ideas on a set of divergent thinking tasks. Also, individuals who excelled at cognitively reappraising the emotionally-distressing stimuli were higher in the personality trait of “openness to experience.” This is a broad and multi-faceted personality predisposition typified by tendencies toward flexibly exploring novel ideas, values, and sensations. Openness to experience has repeatedly been found to be linked to creativity (for one meta-analyses see Puryear, Kettler, & Rinn, 2017).

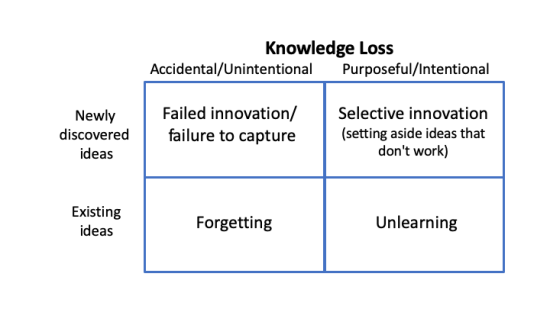

The researchers suggested that the ability to flexibly generate alternative interpretations of a critical situation – an ability that they aptly termed “reappraisal inventiveness” – may be an important contributor to how effectively we can regulate our emotions. Indeed, other research shows that creatively adapting the meaning that we attach to a distressing situation – richly and specifically reframing it in a different way – may help us to beneficially alter how we are emotionally impacted by the event.

Reappraisal, creative restructuring, and the brain

Can we assess the effects of creatively reappraising a distressing event on activity in the brain? Does a highly creative reappraisal exert different neural effects than a merely humdrum (ordinary) reappraisal? These were the questions that an international team of researchers from labs in Beijing and New York banded together to address using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).

The stimuli the team chose were negative and emotionally-arousing pictures (such as threat or attack scenes and disgusting things) selected from a standardized set of emotional images (the International Affective Picture System or “IAPS”). Each image was associated with three different interpretations: a creative interpretation, a typical or ordinary interpretation, and an objective description of the image.

In the MRI scanner, participants were initially shown each negative image for 2 seconds. Then they were shown the negative image again but together with one of the three kinds of text. They were asked to silently read the description and given 12 seconds to try to vividly understand the context it set for the image. After this period of “guided reappraisal,” the negative image was again shown all by itself. Across the scanning session, each participant saw the same set of images but the accompanying text for any given picture was randomly assigned for each participant.

Participants in-scanner ratings of the images showed that participants’ emotional responses to the negative images were significantly less negative (and rated as more pleasant) after they read the creative reinterpretation. Ordinary reappraisals also elicited more positive emotional ratings than did objective descriptions.

These guided-reappraisal differences in participants’ emotional responses were accompanied by several brain activity differences. Compared with the other conditions, creative reinterpretation was associated with significantly greater activity in core emotion- and memory-processing brain regions (the amygdala and hippocampus), and reward-related processing areas (the nucleus accumbens and ventral striatum). Creative reinterpretation trials also showed increased activity in brain regions related to cognitive effort and the monitoring of conflicting information (dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex) and semantic and social cognition (the temporal pole and temporal-parietal junction).

The changes in emotional response that were seen for the negative images that had been paired with a creative reinterpretation were not simply momentary or transient changes. Three days later, when the images were again shown to participants, now without any accompanying text, participants’ emotional ratings of these images were still more positive.

Explaining the reappraisal effect and links to humor

What might be a cognitive explanation for these reappraisal/reinterpretation effects?

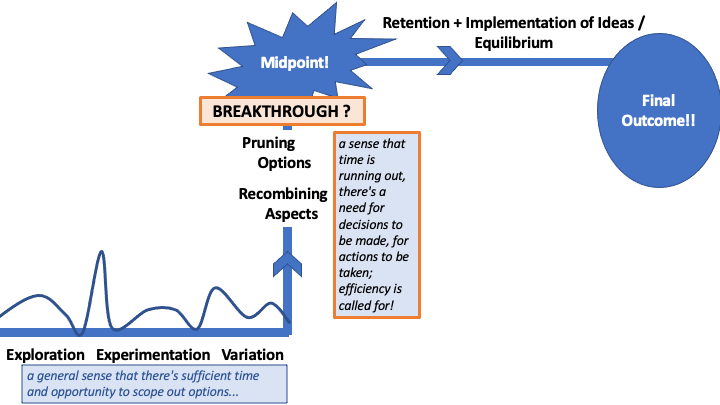

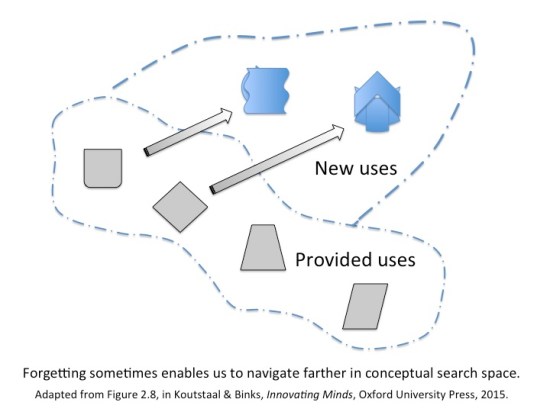

The researchers call attention to how effectively engaging in creative reappraisal may be similar to successful insight problem solving. Arriving at a new insight to a sticky problem on which we’ve reached an impasse often requires us to substantially change how we have been thinking about a problem. We may need to jettison incorrect assumptions that we were unwittingly making, or notice important aspects of the problem that we had earlier failed to even see. Casting off mistaken assumptions, or noticing key details that we’d earlier neglected to see, leads us to re-structure or re-represent the problem. We abruptly see the problem in a different light, or understand it from a different perspective.

This may also be true for what happens when we suddenly see (or others help us to suddenly see) the “funny side” of an emotionally stressful situation. Indeed, a follow-up study by the Beijing/New York research team, now comparing particularly humor-filled reappraisals with ordinary reappraisals, uncovered many similar benefits. Humorous reappraisals led to both greater increases (upregulation) of positive emotion, and more pronounced decreases (downregulation) of negative emotion than was seen for ordinary reappraisal. And these effects, too, were quite enduring as they were still observed 3 days later when the images were shown alone, without any accompanying text.

One of the many benefits of playful humor – introduced in an emotionally stressful moment – may be the cognitive and emotional reappraisal it sparks. Suddenly seeing the ironic twist, incongruity or paradox in the midst of a painful experience can bring not just a smile, but also renewed energy and optimism. Successful emotional reappraisals may, indeed, be creative instances of sudden insightful cognitive reconstruction, and sometimes surprisingly downright funny.

References

Puryear, J. S., Kettler, T., & Rinn, A. N. (2017). Relationships of personality to differential conceptions of creativity: A systematic review. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 11(1), 59–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/aca0000079

Southward, M. W., Holmes, A. C., Strunk, D. R., & Cheavens, J. S. (2021). More and better: Reappraisal quality partially explains the effect of reappraisal use on changes in positive and negative affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research (July, Early Access). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10255-z

Weber, H., de Assuncao, V. L., Martin, C., Westmeyer, H., & Geisler, F. C. (2014). Reappraisal inventiveness: The ability to create different reappraisals of critical situations. Cognition & Emotion, 28(2), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.832152

Wu, X., Guo, T., Tan, T., Zhang, W., Hong, T-Y., Cheng, C-M., Wei, P., Hsieh, J-C., & Luo, J. (2021). From “aha!” to “haha!” Using humor to cope with negative stimuli. Cerebral Cortex, 31, 2238–2250. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaa357

Wu, X., Guo, T., Tan, T., Zhang, W., Qin, S., Fan, J. & Luo, J. (2019). Superior emotional regulating effects of creative cognitive reappraisal. NeuroImage, 200, 540–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.061

You must be logged in to post a comment.